Hydropower Explained: What Is Hydropower & How Does it Work?

Hydropower is electricity produced from any kind of moving water. It’s a renewable energy source and typically cleaner than fossil fuels. However, it’s not as clean or as cost-effective as onshore wind, solar, or geothermal energy. One of its biggest potential uses for the future is as a way to store energy from other renewable power sources.

Topics covered

Picture yourself sitting beside a waterfall. Imagine the water rushing over the rocks and splashing at the bottom, showering you with a cool mist. It’s beautiful—and also powerful. That torrent of water is releasing a large amount of energy as it spills over the falls.

Hydroelectric power, or hydropower, is a way to harness that energy. By directing the water through turbines, we can convert its energy to electricity to power homes and businesses.

What is hydropower?

Hydropower captures the energy embodied in any kind of moving water. It can be a flowing river, water released from a reservoir on high ground, or the tides flowing in and out. A hydroelectric power plant converts that energy to electricity and sends it out into the grid.

The use of moving water as an energy source dates back thousands of years. The ancient Greeks used waterwheels to grind grain more than 2,000 years ago. The first hydroelectric generator was built in England in 1878, producing just enough power to light a single lamp. Today, according to the International Hydropower Association, hydropower plants produce more than 1,330 gigawatts of electricity worldwide.

How does hydropower (hydroelectric generation) work?

Because hydroelectric power depends on moving water, hydropower plants are typically located near a water source. This can be a river, but it doesn’t have to be. Hydropower plants can also capture the energy of flowing water in municipal water facilities or irrigation ditches.

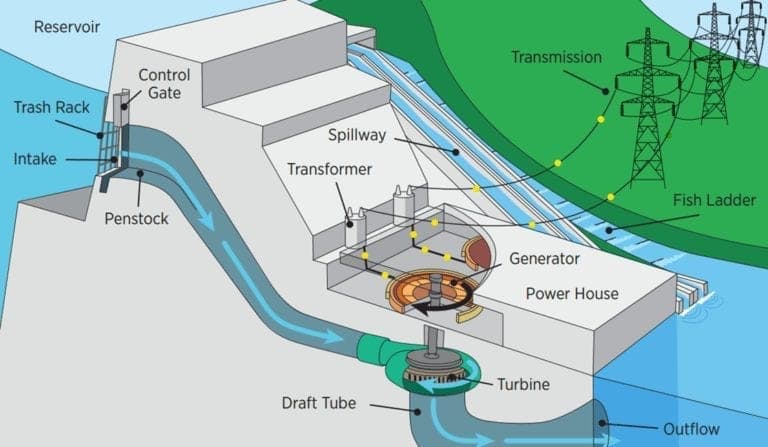

A hydroelectric plant channels all or some of this moving water through a pipe called a penstock. The water moving through the penstock turns the blades of a turbine. This, in turn, rotates a generator to produce electricity.

The biggest hydropower plant in the U.S. is the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington, with a generating power of about 6.8 gigawatts (GW). Each year it produces more than 21 billion kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity—enough to power 2 million homes. But even this facility is only the fifth biggest hydropower plant in the world. It’s dwarfed by the massive Three Gorges Dam in China, which can generate up to 22.5 GW.

However, hydropower facilities don’t have to be large. They come in all sizes, from large facilities producing over 30 megawatts (MW) to “micro” facilities that generate no more than 100 kilowatts. That’s enough to power a single home, a farm or ranch, or even a small village.

The four main types of hydropower

Hydroelectric power plants aren’t always dams. There are actually several types of hydropower facilities that are suitable for different locations.

Dams

The most common type of hydroelectric power plant is a dam, also known as an impoundment. This type of facility blocks up a river to create a reservoir. Gates in the dam can release water from the reservoir and direct it through turbines to produce electricity on demand.

Dams serve a variety of other purposes in addition to providing electricity. The reservoirs they produce can store water for drinking or irrigation. Dams adjust the level of water in the river for flood control or recreation.

Run of the river

It’s possible to harness the power of a river without building a dam. Diversions, also called run-of-the-river facilities, channel a portion of the water through turbines and back into the river. This type of facility relies on the natural slope of the river to produce energy.

In a diversion facility, the water runs through canals or penstocks, or both, equipped with gates and valves to control its flow. These conduits direct the water through a powerhouse containing a turbine and a generator. From there, it’s released back into the river.

Pumped storage

Pumped storage is different from other forms of hydropower. Instead of capturing the energy of flowing water, it stores energy from other sources, such as wind and solar, for later use.

A pumped storage facility has two reservoirs, one on higher ground than the other. When the demand for energy is low, it pulls power from the grid to pump water from the lower reservoir to the upper one. Later on, when the need for energy is higher, it releases this water to turn turbines. This produces electricity to send back into the grid.

There are two kinds of pumped storage facilities. An open-loop facility uses a naturally moving body of water as its lower reservoir. A closed-loop facility contains two artificial reservoirs and moves water between them.

Pumped storage is the main form of energy storage in the U.S. electric grid today. As of 2021, there are 43 plants that can store over 21GW of electricity. In future, we could potentially build enough new pumped storage plants to double that capacity.

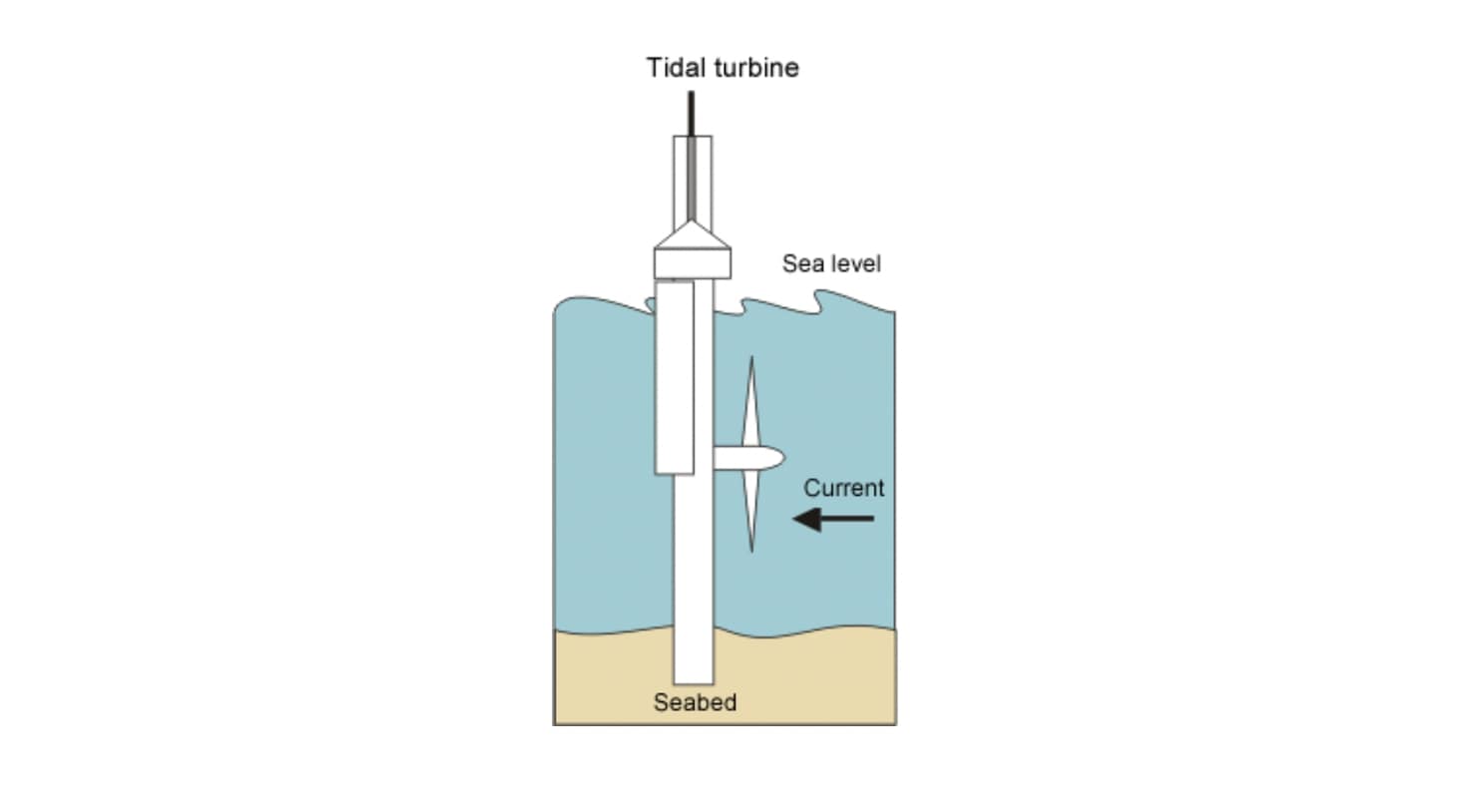

Tidal power

Most hydropower plants use the power of water flowing downhill to turn turbines. Tidal power, by contrast, relies on the flow of ocean tides moving in and out. Ways to capture tidal power include:

- Placing turbines in a tidal stream, a narrow channel where tidal waters move rapidly

- Building a dam-like structure, called a tidal barrage, across an ocean inlet

- Placing a row of vertically mounted turbines, called a tidal fence, on the seabed

- Enclosing a large section of ocean to form a tidal lagoon and positioning turbines where the water moves in and out

How much does hydroelectric power cost?

Hydroelectric power plants can be very costly to build. In its 2021 U.S. Hydropower Market Report, the U.S. Department of Energy looks at the cost of all hydropower plants built in the U.S. between 2005 and 2020. It says these facilities varied widely in price, from under $2,000 to nearly $10,000 per kW. The average cost was $4,000 to $5,000 per kW.

However, that’s a one-time cost. A hydropower plant lasts a long time, and once it’s built, it doesn’t have any fuel costs. A better way to measure the cost of hydropower is its levelized cost of energy, or LCOE. That’s the lifetime cost of producing and maintaining a plant divided by all the energy it produces.

A 2022 report from the U.S. Energy Information Administration compares the costs of different types of newly built power plants. It finds that the LCOE for hydropower plants is $64.27 per mWh. That’s less than the cost for several other types of plants, including coal, nuclear, and biomass. Compared to offshore wind plants, it’s less than half the cost.

On the other hand, hydropower plants have a higher LCOE than solar, onshore wind, geothermal, or natural gas plants. So, as energy sources go—even renewable energy sources—hydropower isn’t the most cost-effective.

Is hydroelectric energy renewable or nonrenewable?

Hydropower is renewable because you can’t use it up. Any water you use to generate electricity will evaporate into clouds and eventually fall back down as rain. This natural process, called the water cycle, is continuous. So, no matter how much of a river’s water you use to generate electricity, there will be more where that came from.

Hydropower is the biggest source of renewable power worldwide, producing more than 70% of all renewable energy. Within the U.S., it produces over 30% of renewable energy and about 6% of all energy. Nearly every state in the country has at least one hydropower plant.

How does hydropower affect the environment?

Although hydropower is renewable, that’s not the same as being green. Some critics of hydropower argue that it isn’t truly sustainable because it can harm the environment in several ways.

Impact on wildlife

Damming up rivers and ocean inlets can change the temperature, chemistry, and amount of silt in the water. These changes harm plants and animals that depend on the river or ocean ecosystem. Dams can also interfere with the migration of fish such as salmon and steelhead trout.

There are ways to reduce the impact hydropower has on wildlife. Dams can include “fish ladders,” or fishways, to help fish navigate past the blockage. They can use fish-friendly turbines that are less likely to trap and kill fish. And they can pull water from different parts of a reservoir to control its temperature better.

Climate impact of dam construction

Another problem with dams is the materials used to build them. Concrete and steel are high-impact materials that require a lot of energy to produce. That means that before a hydropower dam even starts generating energy, it has already produced a lot of carbon emissions.

The best way to mitigate this problem is to keep the dam in use as long as possible. Then the clean power it produces can offset the emissions from its construction.

Decaying biomass

A hydropower plant’s carbon footprint doesn’t come only from the materials that go into it. Building a reservoir means covering large amounts of plant matter with water. As this material decays, it releases greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane.

Levels of these emissions vary widely from one reservoir to another. The worst hydropower plants produce more emissions over their lifetime than some fossil fuel plants. Being more selective about where to build hydropower plants—and which existing plants to keep—could help reduce the emissions problem.

What are the advantages of hydroelectricity?

There are several advantages of hydroelectric power as a way to produce electricity—especially compared to fossil fuels. Hydropower is:

- Renewable. Unlike fossil fuels, hydropower is an energy source that can never run out.

- Clean. Tapping into a river for hydropower doesn’t pollute or consume the water. And while hydropower produces some greenhouse gases, it’s generally cleaner than most fossil fuels.

- Efficient. The best hydropower facilities can convert over 90% of the energy stored in the water to electricity. By contrast, the best fossil fuel plants can only extract about 60% of the energy in the fuel.

- Continuous. A hydropower plant can generate electricity at any time. That gives it an advantage over wind and solar, which only produce power when the wind blows or the sun shines.

- Flexible. Many hydropower plants can quickly adjust the amount of power they produce to match the demand for electricity.

- Locally produced. Nations that use hydropower don’t have to rely on fuel imported from other countries.

- Stable in price. Because hydropower is continuous, it doesn’t fluctuate in price the way fossil fuels do.

- Useful for storage. Pumped hydropower can store energy from other renewable sources, such as wind and solar. Although the cost of hydropower is only so-so as a way to generate power, it’s only about half as expensive as batteries and other ways to store power.

Are there any drawbacks to hydroelectricity?

Despite its many benefits, hydropower has some serious drawbacks compared to other renewable power sources. These include:

- High up-front cost. Hydropower facilities are expensive and time-consuming to build.

- Middling affordability. Although hydropower is more affordable than many existing power sources, it’s not as affordable as solar, onshore wind, or geothermal.

- Limited locations. Most types of hydropower plants must be built near a source of running water. Closed-loop pumped storage doesn’t require a water source, but it does require a difference in elevation between the two reservoirs.

- Dependence on rainfall. Most of the time, hydropower is a reliable energy source. But during a drought, the water flow in rivers falls, and the energy output from hydropower plants drops with it.

- Environmental costs. Dams can harm wildlife in and near rivers. Hydro plants also produce some greenhouse gas emissions from their construction and from decaying plant matter.

The future of hydropower

For many years, hydropower was the main way to produce clean, renewable energy. During that time, many new hydropower plants went up, becoming a major power source in some areas. Many of these existing hydroelectric plants will continue to provide power for years to come. Since the financial costs and environmental costs of their construction have already been paid, it makes sense to keep them running and get as much low-cost, low-polluting energy from them as possible.

However, the benefits of building new hydroelectric plants are less clear. Today other renewable energy sources, like onshore wind and solar, are more cost-effective than hydropower. They’re also easier to build in different areas and have lower environmental costs. So, in future, these sources are likely to become more important than hydropower for producing energy.

Hydropower still has a part to play in a clean energy future. Existing hydroelectric plants can supplement new sources like wind and solar, helping us get to a fully renewable grid faster. And pumped hydro will remain a useful source of energy storage, making green power available round the clock. But hydropower’s role will probably diminish as new energy technologies become steadily cheaper, cleaner, and easier to use